The Chinese government has promised new child care subsidies, increased wages and better paid leave to revive a slowing economy. That is on top of a $41bn discount programme for all sorts of things, from dishwashers and home decor to electric vehicles and smartwatches.

Beijing is going on a spending spree that will encourage Chinese people to crack open their wallets.

Simply put, they are not spending enough.

Monday brought some positive news. Official data said retail sales grew 4% in the first two months of 2025, a positive sign for consumption data. But, with a few exceptions like Shanghai aside, new and existing home prices continued to decline compared to last year.

While the US and other major powers have struggled with post-Covid inflation, China is experiencing the opposite: deflation – when the rate of inflation falls below zero, meaning that prices decrease. In China, prices fell for 18 months in a row in the past two years.

Prices dropping might sound like good news for consumers. But a persistent decline in consumption – a measure of what households buy – signals deeper economic trouble. When people stop spending, businesses cut prices to attract buyers. The more this happens, the less money they make, hiring slows, wages stagnate and economic momentum grinds to a halt.

That is a cycle China wants to avoid, given it’s already battling sluggish growth in the wake of a prolonged crisis in the property market, steep government debt and unemployment.

The cause of low consumption is straightforward: Chinese consumers either don’t have enough money or don’t feel confident enough about their future to spend it.

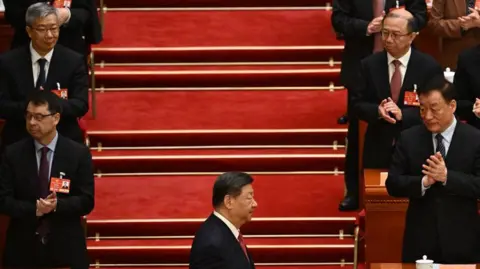

But their reluctance comes at a critical moment. With the economy aiming to grow at 5% this year, boosting consumption is a top priority for President Xi Jinping. He is hoping that rising domestic consumption will absorb the blow US tariffs will inflict on Chinese exports.

So, will Beijing’s plan work?

China is getting serious about spending

To tackle its ailing economy and weak domestic demand, Beijing wrapped up its annual National People’s Congress last week with increased investment in social welfare programmes as part of its grand economic plan for 2025.

Then came this week’s announcement with bigger promises, such as employment support plans, but scant details.

Some say it is a welcome move, with the caveat that China’s leaders need to do more to step up support. Still, it signals Beijing’s awareness of the changes needed for a stronger Chinese consumer market – higher wages, a stronger social safety net and policies that make people feel secure enough to spend rather than save.

A quarter of China’s labour force is made up of low-paid migrant workers, who lack full access to urban social benefits. This makes them particularly vulnerable during periods of economic uncertainty, such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Rising wages during the 2010s masked some of these problems, with average incomes growing by around 10% annually. But as wage growth slowed in the 2020s, savings once again became a lifeline.

The Chinese government, however, has been slow to expand social benefits, focusing instead on boosting consumption through short-term measures, such as trade-in programmes for household appliances and electronics. But that has not addressed a root problem, says Gerard DiPippo, a senior researcher at the Rand think tank: “Household incomes are lower, and savings are higher”.

The near-collapse of the property market has also made Chinese consumers more risk-averse, leading them to cut back on spending.

“The property market matters not only for real economic activity but also for household sentiment, since Chinese households have invested so much of their wealth in their homes,” Mr DiPippo says. “I don’t think China’s consumption will fully recover until it’s clear that the property sector has bottomed out and therefore many households’ primary assets are starting to recover.”

Some analysts are encouraged by Beijing’s seriousness in targeting longer-term challenges like falling birth rates as more young couples opt out of the costs of parenthood.

A 2024 study by Chinese think tank YuWa estimated that raising a child to adulthood in China costs 6.8 times the country’s GDP per capita – among the highest in the world, compared to the US (4.1), Japan (4.3) and Germany (3.6).

These financial pressures have only reinforced a deeply ingrained saving culture. Even in a struggling economy, Chinese households managed to save 32% of their disposable income in 2024.

That’s not too surprising in China, where consumption has never been particularly high. To put this in perspective, domestic consumption drives more than 80% of growth in the US and UK, and about 70% in India. China’s share has typically ranged between 50% to 55% over the past decade.

But this wasn’t really a problem – until now.

When shopping fell and savings rose

There was a time when Chinese shoppers joked about the irresistible allure of e-commerce deals, calling themselves “hand-choppers” – only chopping off their hands could stop them from hitting the checkout button.

As rising incomes fuelled their spending power, 11 November in China, or Double 11, came to be crowned as the world’s busiest shopping day. Explosive sales pulled in over 410 billion yuan ($57bn; £44bn) in just 24 hours in 2019.

But the last one “was a dud,” a Beijing-based coffee bean online seller told the BBC. “If anything, it caused more trouble than it was worth.”

Chinese consumers have grown frugal since the pandemic, and this caution has persisted even after restrictions were lifted in late 2022.

That’s the year Alibaba and JD.com stopped publishing their sales figures, a significant shift for companies that once headlined their record-breaking revenues. A source familiar with the matter told the BBC that Chinese authorities cautioned platforms against releasing numbers, fearing that underwhelming results could further dent consumer confidence.

The spending crunch has even hit high-end brands – last year, LVMH, Burberry and Richemont all reported sales declines in China, once a backbone of the global luxury market.

On RedNote, a Chinese social media app, posts tagged with “consumption downgrade” have racked up more than a billion views in recent months. Users are swapping tips on how to replace expensive purchases with budget-friendly alternatives. “Tiger Balm is the new coffee,” said one user, while another quipped, “I apply perfume between my nose and lips now – saving it just for myself.”

Even at its peak, China’s consumer boom was never a match for its exports. Trade was also the focus of generous state-backed investment in highways, ports and special economic zones. China relied on low-wage workers and high household savings, which fuelled growth but left consumers with limited disposable income.

But now, as geopolitical uncertainties grow, countries are diversifying supply chains away from China, reducing reliance on Chinese exports. Local governments are burdened by debt, after years of borrowing heavily to invest, particularly in infrastructure.

Xi Jinping has already vowed “to make domestic demand the main driving force and stabilising anchor of growth”. Caiyun Wang, a National People’s Congress representative, said, “With a population of 1.4 billion, even a 1% rise in demand creates a market of 14 million people.”

But there’s a catch in Beijing’s plan.

For consumption to drive growth, many analysts say, the Chinese Communist Party would have to restore the consumer confidence of a generation of Covid graduates that is struggling to own a home or find a job. It would also require triggering a cultural shift, from saving to spending.

“China’s extraordinarily low consumption level is not an accident,” according to Michael Pettis, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “It is fundamental to the country’s economic growth model, around which three-four decades of political, financial, legal and business institutions in China have evolved. Changing this won’t be easy.”

The more households spend, the less there is in the pool of savings that China’s state-controlled banks rely on to fund key industries – currently that includes AI and innovative tech that would give Beijing an edge over Washington, both economically and strategically.

That is why some analysts doubt that China’s leaders want to create a consumer-driven economy.

“One way to think about this is that Beijing’s primary goal is not to enhance the welfare of Chinese households, but rather the welfare of the Chinese nation,” David Lubin, a research fellow at Chatham House wrote.

Shifting power from the state to the individual may not be what Beijing wants.

China’s leaders did do that in the past, when they began trading with the world, encouraging businesses and inviting foreign investment. And it transformed their economy. But the question is whether Xi Jinping wants to do that again.